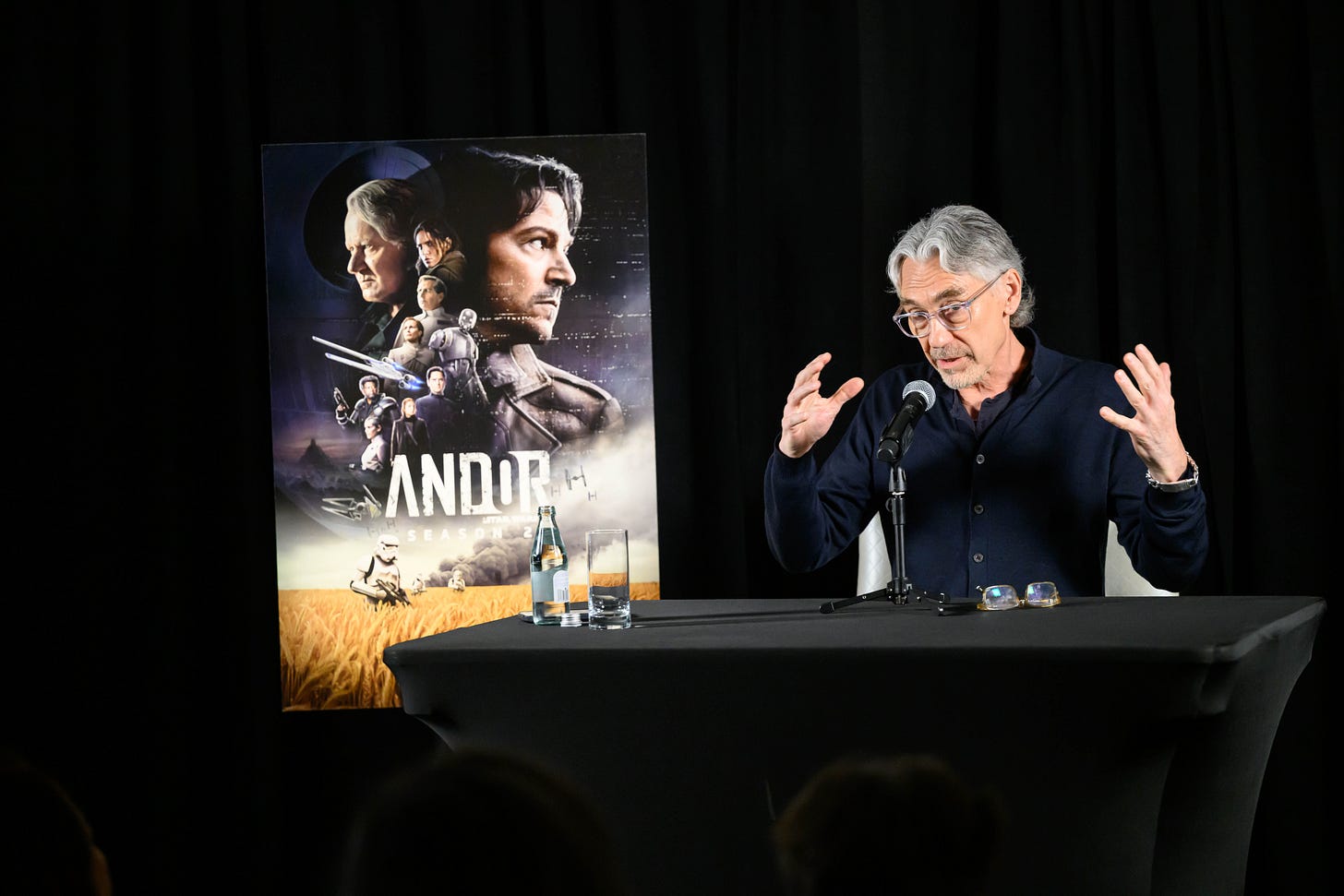

'Andor' Q&A: Tony Gilroy

The creator of Andor on revolution, risk, and redefining what Star Wars can be

The second season of Andor brings the story of rebellion to its turning point, and behind it all is creator and showrunner Tony Gilroy, returning to finish what he started with Rogue One.

The award-winning writer, director, and producer is known for his sharp writing and tightly wound political thrillers — including the Bourne franchise, Michael Clayton, and of course, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story — bringing a more grounded sensibility to the Star Wars universe.

On April 15, 2025, voters in the Golden Globes were invited to a press Q&A with Gilroy to discuss the making of Andor. The session was held at the Four Seasons in Los Angeles and streamed on Zoom.

Over the course of the conversation, Gilroy spoke candidly about the scope and complexity of producing Andor, the challenge of writing messy, human characters, the influence of history on the show's themes, and why he chose to end the series with its second season.

Here is the Q&A with Tony Gilroy. Fair warning: there are a couple of very minor spoilers ahead. Why? Because this is a Q&A, and I would never presume to censor anything Mr. Gilroy says.

Q: What was your relationship with Star Wars before Rogue One, and how has it changed through Andor?

Tony Gilroy: I mean, I saw the first film in 1977. I watched the first trilogy, for sure. No secret, it was never my thing, or my first choice.

I wasn’t on the bus with that at all. I came on Rogue as a doctor, you know? A mercenary. Pretty much like Cassian Andor. I was a mercenary. And in a strange way—and this has benefited me before in many things—not knowing, not caring is a superpower when people are in trouble. When something’s not working, it doesn’t help to be a fan.

I was a mercenary.

So, on Rogue, it was a very different experience. And I don’t talk about that in much more detail than I just did. But that was a very clinical experience.

This is completely different. This is like giving blood. I mean, this has been from the start. This is all in. It was a very, very different experience.

And then I learned a little bit of what I had to learn. But you know, the request was to really take the Latin mass out of the church. They wanted to change the grammar, they wanted to do things. So, it didn’t behoove me to go back and fall in love with Wookiees and lightsabers and stuff. It wasn’t helpful to what I had to do.

But yeah, my experience here—you can tell how plugged in I've been for five years.

And just to speak about hope, I would’ve been really disappointed if we didn’t finish the story on hope. I mean, it’s like a T-shirt: rebellions are built on hope. But it’s really true. If we don’t have that—if that light goes out—then I don't know how we would go on.

That was always the idea. I do want to be positive at the end, as heavy as it all is. And I think the people who make history—a lot of times—are all the people that are forgotten. A lot of these characters in the show, they’re the gravel in the road on the way to liberation.

A lot of these characters in the show, they’re the gravel in the road on the way to liberation.

And how many people in history are absolutely essential to where we are, and then the real heroes—you never heard of them. So, you really have to have something hopeful at the end to justify their sacrifice.

Q: Why did you decide to end Andor with season two, rather than continuing beyond that?

Tony Gilroy: We could’ve. We had no idea. I can’t overemphasize the ignorance and naivety I had when we started—really, that we all did.

I went to London, we started casting, and I was supposed to direct three episodes in the spring. The scripts were coming in, and I realized I had to rewrite mine, rewrite the others. If COVID hadn’t happened, it would’ve been a disaster. Seriously. COVID shut everything down, and honestly, I was hoping the show would go away. I was just beginning to grasp what we’d signed on to. We made a huge mistake.

But COVID reset the show. We built a whole new system and learned how to make it properly. When I finally got back out of quarantine and up to Scotland to shoot, I sat with Diego and we were like—there’s no way we could do five seasons. It would take fifteen years. He’d be 60 years old. Even with de-aging, it’s just too hard. The scale of what we were doing… it wasn’t realistic.

So we found the solution, and it presented itself: four blocks, four years. There was no way we could do more than we’ve done. And if the show is good, it’s because we always had an ending.

If the show is good, it’s because we always had an ending.

When we started the second season, we knew we had to cash the check—we’d made the investment, and now we had to finish stronger than we started. We also knew we were sprinting to the end, pouring everything we had into it.

And I’m not sure the show would be as good if it were open-ended. I don’t think it would be.

Q: Beyond the actors, what will you miss most about working on Andor?

Tony Gilroy: Oh, man. I mean, look—for five years, literally—I’m an exaggerator for sure, but I get paid to exaggerate—every single day was maximal. Imaginative. Everything I ever learned: all the design, all the casting, everything we do. All the writing and rewriting and tuning and problem-solving.

I lived in my head. Just pure imagination for five years, every single day. It’s a really powerful drug, and it’s a great place to hide out. And I miss that, you know? I miss that.

And you know, as showrunner, you get a lot of places to taper off. There are a lot of endings. I think we’ve all realized this in the last couple of weeks—that the show really is about… people can put whatever ideological spin they want on it.

But the most beautiful, the simplest, and the least controversial idea is that it’s about community. The value of community. And the empire, the fascists, the authoritarians—whatever you want to call them—they are the destruction of community on every level. The smallest level and the highest level.

It’s kind of fascinating to make a show where, at its core, community is the church. And the people making it are a community. You can see how much everybody cared. I had a friend who came to the screening last night, and we were all on stage, and he wrote me—he’s made a lot of movies. He said, “I don’t know how you got through five years, but it actually looked like you were happy together.” Not at each other’s throats.

So, to build a community that’s vaguely utopian while making a show about the destruction of community—that was powerful. I’ll miss that.

Q: What did you learn about producing and budgeting a large-scale series like Andor, especially as audience expectations kept evolving?

Tony Gilroy: Wow, complicated question. I mean, fascinating question. You could do hours on that.

You know, look, in a nutshell, we started this—it was almost like Pearl Harbor. It was literally: we need big shows, big shows. Build us a cathedral. Build an aircraft carrier. That was the mandate. Thrones was out there. Streaming was going to be everything. So, the mandate in the beginning was adhesion. We said we’d do eight episodes. They said they wanted twelve. And so, it was like, okay. Scale was everything.

So, we built a machine that would make that first season. And I’ll come back to the system in one second. The second season—by the time we’re releasing, because it takes so long to do the show—by the time we’re releasing and starting to do the second season, well, as you well know, that had really, really changed. Everything had contracted. Streaming wasn’t the golden goose everyone thought it was going to be.

That was a really big awakening for everybody and a lot of really challenging decisions for us, for Disney. And a really big gamble. Iger had come back, and you’re asking for a lot of money, and they’re laying people off. It’s very complicated. What do you do? And we didn’t have a skinny version of the show. It’s sort of like furnishing Versailles or something. You can’t put IKEA furniture in. You can’t.

Our philosophy about making this show, however, was one of the things that let us continue. We never wasted a penny. We never wasted anything. We reshot one thing in the opening sequence, just because we thought the directors were being timid and we wanted them to be brave. We used everything. I would say we were probably one of the most efficient shows they’ve ever had on the network.

So, we prepped like crazy. We were very expensive, but every single thing we get goes up on screen. I think that’s the key to working big. I know there are a lot of other big shows where you see waste and you see reshoots and rebuilds and everything else. We never did anything like that. Everything we did was precise, all the way down the line.

And I think the critical wind we got from the first season—those are the things that let us just slip through and gave them the confidence to gamble. That’s a long answer to a question, but it’s a very big topic.

Q: Season two moves between different time blocks. What happens in the periods we don’t see, and how did you and the cast approach that off-screen development?

Tony Gilroy: Look, I mean, when we came up with the idea—we were literally sitting, drinking with Diego in Pitlochry in Scotland, freaking out, like, what are we gonna do? And when the idea for the four blocks and the four years came up—and I wish I could pretend it was some genius idea—but it was a problem-solve.

It was like, oh my God, look at that. We have four years. We have these four things. I remember going back up to the hotel room, turning on the computer, sketching—what would that be like? And oh my God, if we only come back for a couple days each time, that’s intense. So I knew everybody would be suspicious of it, so I wrote the first and last scene of each block. I sketched each one, just as a proof of concept to see how they’d work. And what you find when you do that is: I knew what had happened in between because the people behave the way they behave when they come back.

There are a couple places where the actors needed to know something specific. In four, Adria and Diego really needed to know a lot about the incident that happens before you’re in the safehouse—what have we been doing? What’s it been like? How’s it been? But shockingly, as we went along, the questions became fewer and farther between. And I’ll answer any questions that actors have, but they really were all comfortable with where they started.

And our show is so much about the moment—moment to moment to moment. If you’d asked me before we started, I would’ve said, oh my God, we’re going to write a whole bible of everything that happened in between. We never had to do it. It worked much more easily and effortlessly than I had ever anticipated. Yeah—surprising.

Q: You introduced many new actors across Andor, several of whom became breakout stars. What do you look for when casting—and how important is the supporting cast to the show’s success?

Tony Gilroy: Our superpower in this show has been the casting—Nina Gold and Martin Ware. And you all know Nina. She’s cast all the shows. We had four hundred speaking parts across the two seasons. I just kept writing lots of characters and driving everyone crazy doing that.

An American showrunner told me before I went over, “You’re gonna be so happy. You’re gonna go to Nina, and she’s gonna bring in all these actors you’ve never seen before. British directors won’t hire them because they were on East Enders or Coronation Street or did some bad milk commercial. They’re snobby about it. But to you, they’ll be fresh, and they’ll be fantastic.”

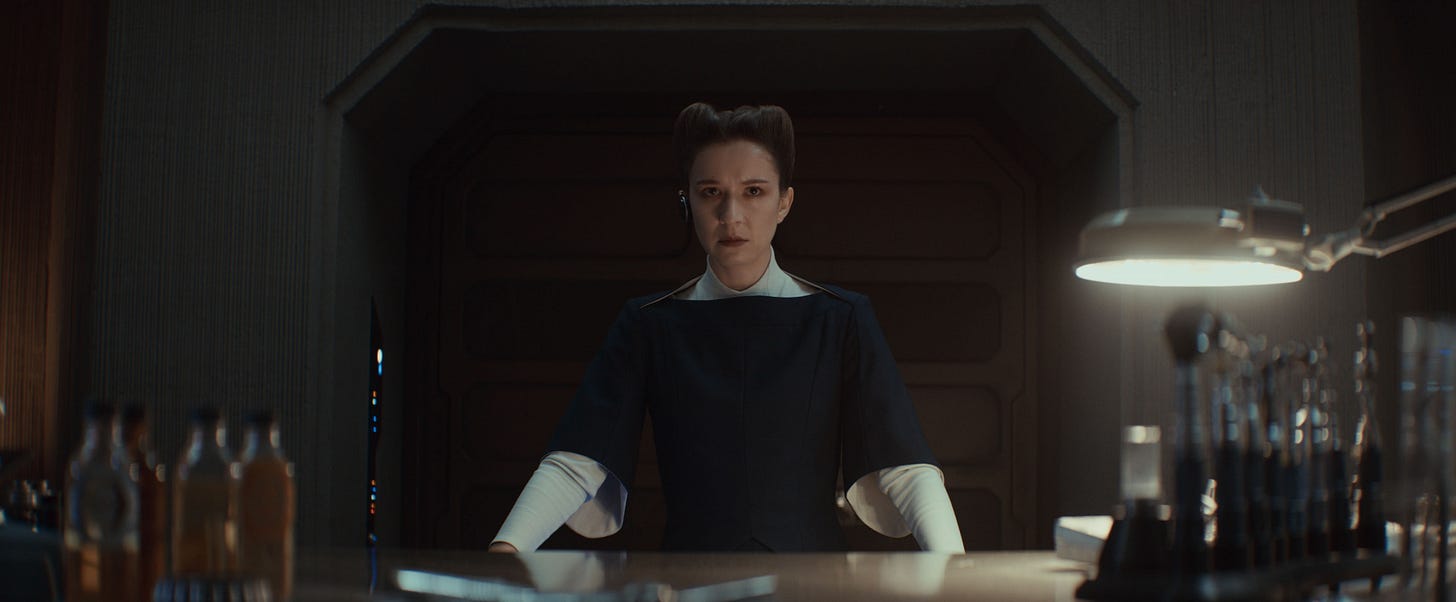

Man, the talent pool in the UK—it was extraordinary. Nina just kept bringing people in. Elizabeth Dulau, who plays Kleya—she came right out of RADA. First job. We threw her in with Stellan. If she hadn’t worked out, she could’ve just been the sorcerer’s apprentice and we’d carry her longer. But oh my God. Look at this. So you just start writing for that person.

Man, the talent pool in the UK—it was extraordinary.

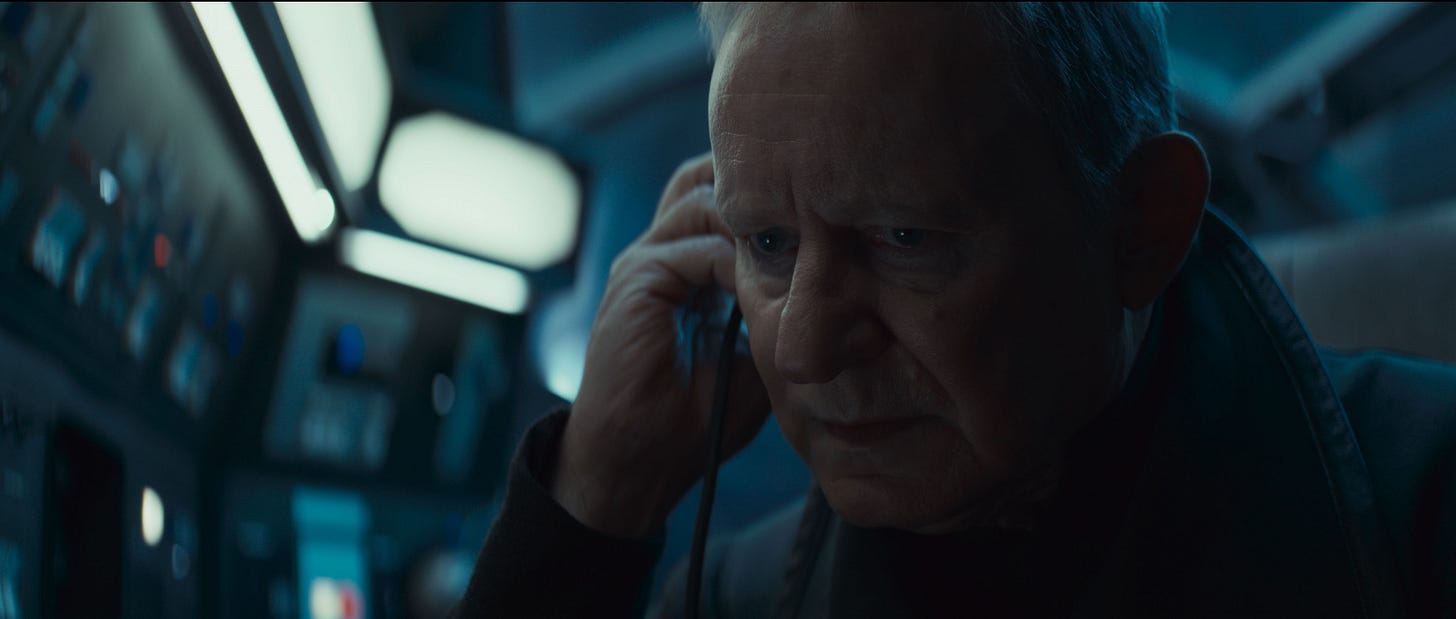

Mo, who plays Wilmon—I threw him on the truck at the end to save him. But look what he can do. Genevieve—have to hire her. She’s legacy. Comes with a thing. I knew her from Rogue. But I didn’t know what she could do. Turns out—she can do anything.

And it goes on and on with day players and people all the way through. Anton Lesser as Partagaz. I could just go on. But the selfish byproduct for me—even at this late date in my career when I should be degrading—I became a much better writer from this show. Because I knew who I was writing for. I knew the orchestra I was writing for. I knew the instruments were in tune. I knew everybody could do all these things.

So you just get inspired. You’re watching dailies every morning. Everything that comes off the desk is going into production. I wish I could take the writing skills I have now and go back 30 years and start over again. I really learned a lot from these actors. I know that seems weird, but that’s my takeaway.

Q: How has your idea of the hero evolved over time—and what makes Diego Luna’s portrayal of Cassian so compelling?

Tony Gilroy: I've been in the hero business a long time, right? No, I mean, you have to want to be them, you know? There has to be something in them that people want to be. I think that’s essential.

But I think there’s another answer, as well. If you ask me, over—I don’t even want to say how many decades I’ve been doing this, you can look me up—you know how long I’ve been around. The biggest change as a writer in my career? Two things. One, time—being able to just do a show like this. Time is a new dial. You can do twelve, twenty-four episodes. But I think The Sopranos really did something so fundamental to every meeting and every conversation. I have a cartoon from The New Yorker on the wall of my office, and it’s two cavemen, and on the wall there’s a hunter about to spear a woolly mammoth. And one guy is saying to the other guy, “Can you make the hunter more sympathetic?”

And, like, everybody had to be sympathetic. And after Tony Soprano, everybody realized, they just have to be fascinating. You have to be able to find something to see into them. So I think the level of complexity we have now—we should hang on to that. But you’ve got to be able to relate. You’ve got to want to be that person.

Man, everything you see from Diego—his inner goodness is inescapable. No matter when he’s killing the cops or whatever he’s doing. I mean, you know him and you’ve been around him. He’s just a wonderful human being. And I’ve been with him for ten years now. We’ve never had a disagreement. He’s just the best partner ever.

So no matter what he does, no matter how venal or ugly it is, you always feel that there’s this little bit of a halo still burning inside him. That’s really helpful. And he’s able to convey—the show is very messianic in a way, right? I mean, he’s a messianic figure. And I don't know how many people here have seen the second season, but you see him reluctantly not wanting that destiny. He manages to keep marching forward, and yet keep a little bit of chaos in there all the time, as well. And I think we’re fascinated by chaos in characters. And I don't know. Some of it’s magic, too, right?

Q: As you built the bridge between Andor and Rogue One, did anything from the film need to be adjusted—or did it all align smoothly?

Tony Gilroy: No, there’s a couple of things—we had to reality check some of what happened in Rogue so we didn’t violate anything. But the really cool thing about starting it was the casting of Andor. He’s this all-singing, all-dancing, perfect warrior spy. He’s an amazing leader—someone who can lie, seduce, change his mind, plan. Obviously, they trust him with this incredible mission.

So my concept was: let’s take him back five years and make him a roach. Let’s pick him up on the worst day of his life and watch this roach become a butterfly. That was my thesis.

And the cool thing about Rogue One is it moves so fast. He’s so enigmatic. The little bits and pieces—the breadcrumbs—were exactly what we needed. He’s not overexposed in Rogue. So, just in terms of justification, it was perfect. But there wasn’t anything I needed to change, no.

Q: The series explores propaganda and information warfare—governments using misinformation to shape public perception. Why was that important to include?

Tony Gilroy: Power always wants to control the narrative, right? I've been asked that question a lot, and people act like it’s a fresh idea.

The burning of the Reichstag—so you can get rid of the Communists and Jews and blame it on them. The Gulf of Tonkin—bullshit that brings America into Vietnam. William Randolph Hearst sells the Spanish-American War with the blowing up of the Maine. I think since the very first campfire, someone’s wanted to control the story. Control the story, and you control a lot.

And it would've been no fun—forget irresponsible, just no fun—to get one chance in my life to do this big novel about revolution and insurrection and not get everything in. I want all of it. I have so many things to talk about and so many people to do it with.

So yeah, I had to deal with that. I had to deal with propaganda. I had to deal with manipulation. And the takedown of Ghorman is there from the very first scene—with Ben Mendelsohn talking about the possibility of destroying Ghorman. That’s based on the Wannsee Conference. That’s literally where it came from for me.

Yeah, I mean, power takes the microphone.

Q: The themes in Andor have been described as a warning against authoritarianism. Was that your intent—and how do you see the show reflecting the current world?

Tony Gilroy: I mean, obviously with the strike, the show should’ve come out a year ago. We pretty much built this four or five years ago. Didn’t write it with a newspaper.

The reason I came on the show was they said, okay, you can have this massive canvas to work with, all these resources, and Diego. And you can do the definitive survey of revolution, insurrection, and authoritarian power. I’d been studying that my whole life with no place to use it. I spent my whole life reading history, and I was like, oh my God—I can do all these things here.

I spent my whole life reading history, and I was like, oh my God—I can do all these things here.

For me, the show was always timeless. I’m pulling things from six thousand years of history: the Haitian Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the American Revolution, the British Revolution. Early Catholicism. Every single thing—every book about Zapata I ever read—I could put everything in there.

I think it’s really sad. The moments of peace and prosperity throughout history are in very short supply. Most of history is rinse and repeat—this sad story. I think if you showed this to somebody a hundred years ago, three hundred, four hundred years ago, or three hundred years from now, it would still be relatable.

I don’t know, I’m not psychic. I wasn’t psychic to get us here, and I’m not psychic to predict what will happen when the show is released. And we shall see—and you can see me dancing around this question.

Q: Season two feels more grounded in espionage and intelligence. Were there any specific films or shows that influenced that direction?

Tony Gilroy: Yeah, I mean, all the spy stuff—I’ve been doing that forever. I didn’t really have to study up on it again. A lot of what I already knew, like things about the French Resistance, was useful for some of what we did.

As for influences—yeah, I’ll go international. Le Village Français. I love that show. I was watching it around the time I was building this. My wife and I went all the way through it.

What I learned from that show is how you can have a huge volume of decisions—real, organic decisions—in every episode. You want your characters to be making choices. Not just passive or pushed by plot. That show really delivered on that. Every episode had epic decisions, and that stuck with me.

But I’d say the most inspiring show for me was Babylon Berlin. That show blew me away—how beautiful it was, how rich and complex. That first run of episodes, I don’t know how many there were—eighteen? It was epic. Just the idea that you could do something that complex and gorgeous... that really pushed me. Those two shows were probably the most influential.

Q: You’ve said Andor is the most important thing you’ve ever worked on. What makes it stand apart from projects like Michael Clayton, The Bourne Legacy, or Rogue One?

Tony Gilroy: I mean, when you start doing a show like this... I have a bunch of my cohort—older screenwriters who made a living writing movies. We were trained in the ’80s, came into the ’90s, learned how to button your scenes, get in and out. All the things you had to do to feed your family, right? And then moving past that, to make your own movies.

But I kind of feel like the first three quarters of my career was as a short story writer. And this was an opportunity to be a novelist. Not just to write a novel, but like—an epic novel.

And I’ve said this before—you know, we now have this idea of the sympathetic hero versus the fascinating hero. What’s really cool about writing now, that wasn’t there when I started or even along the way, is that there’s this new dial on your imaginative keyboard: time.

How long should the story really take? You look at something like Godless, Scott Frank’s Godless. That was a script in Hollywood for years. Everybody loved it. But it was a little overstuffed and never got made. It wanted to be six episodes.

You have a story—now, okay, that should be three. This should be eight. That should be twelve. This should be five. It’s such a cool development. And this, for me, was the chance to really stretch out.

That’s what made it so important.

Check out the Q&A with Diego Luna here: