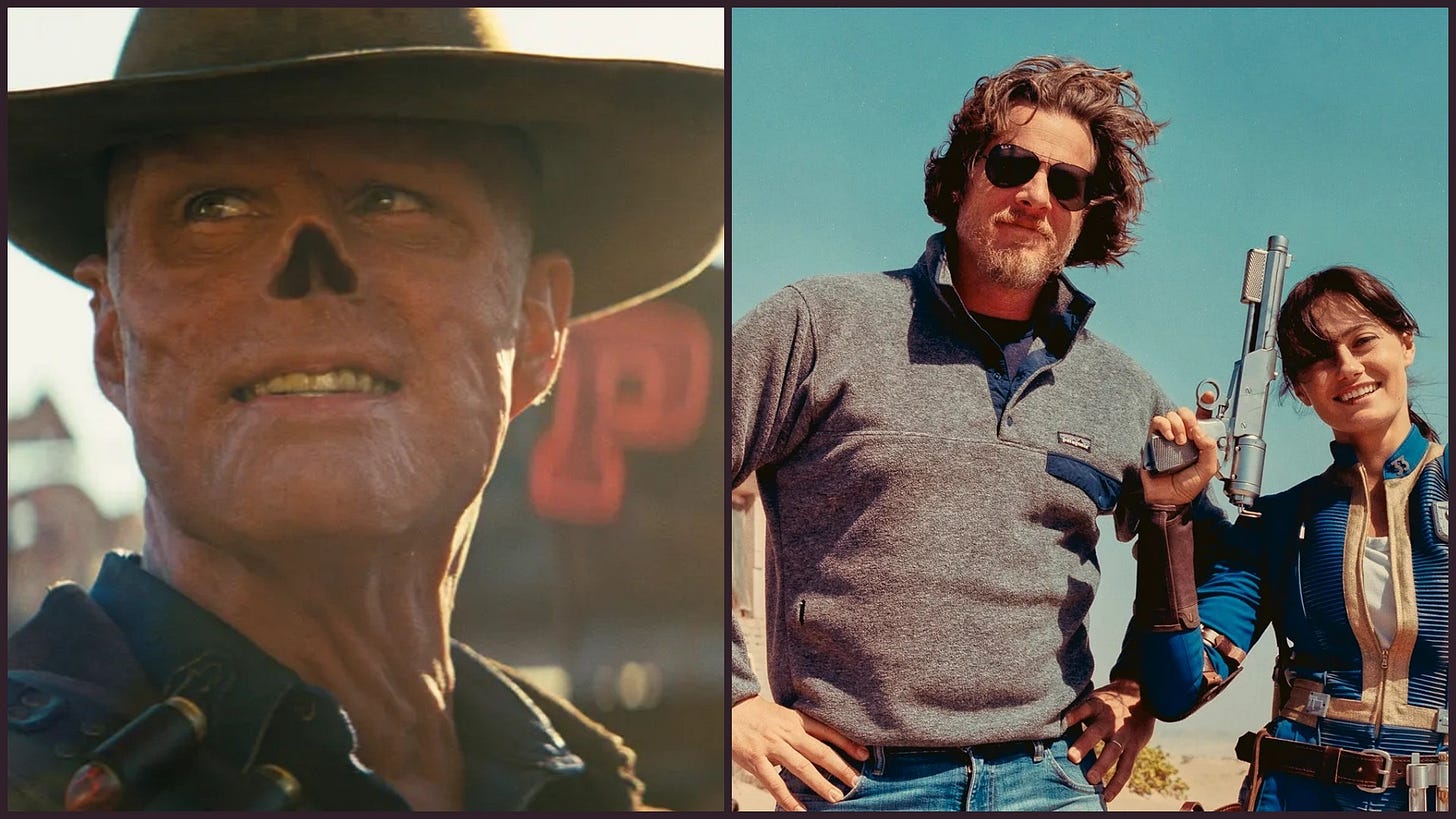

Exploring Fallout with Jonathan Nolan and Walton Goggins

On action, satire, authenticity and breaking the dreaded video game adaptation curse.

Perhaps I’m dating myself a bit now, but I distinctly remember a day as a kid, sitting at our summer home in Norway, playing a game on my computer. I’m sure the weather was bad—or maybe I was just a big nerd.

Either way, the game was the original Fallout. I mean, the first-ever Fallout—a pixelated, isometric role-playing game with (if memory serves) turn-based combat against mutants and radioactive creatures in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

I remember thinking the power armor was so cool. I just had to get my character into one.

As most gaming nerds know, Fallout went on to become a major, iconic franchise. That game I was playing on a rainy summer day in Norway? It kicked off a series that’s still going strong—at least in the hearts of gamers everywhere. I can’t quite recall playing the sequel to that pixelated RPG, but Fallout 3? That’s where things really took off. With its shift to first-person action RPG, biting satire, dark humor, and plenty of bloody gore, it set the bar not just for future Fallout games, but for the genre as a whole.

And last year, we got the TV adaptation. I remember reading about it some years ago—Amazon was working on a series based on the iconic game franchise, and my heart sank. We all knew about the dreaded “video game adaptation curse,” the one that warned us that films and TV shows based on games were doomed to fail.

But if the last few years have taught us anything, it’s that the curse is dead. There’s been a whole slew of successful video game adaptations, both on the big and small screens—The Super Mario Bros. Movie, the Sonic films, The Last of Us, Arcane… and as a World of Warcraft player (yep, still a nerd), I’d even dare to add the Warcraft movie to that list.

And right at the top of that list? Amazon’s Fallout series.

At the tail end of 2024, I joined some of my fellow Golden Globes journalists for a Zoom conversation with producer and director Jonathan Nolan and actor Walton Goggins, who plays the fan-favorite character the Ghoul. We talked about the series—and why it’s become the hit that it is.

Jonathan Nolan has a long history with gaming, though, as he joked, parenthood has made finding the time a bit trickier. “I was a lifelong gamer until my kids showed up, and then the time for recreation went away,” he said.

His love for storytelling in games dates back to the late 2000s, when he noticed a shift in how games were telling their stories. “I think for me, in the late 2000s was when I really started to notice that narrative in games was getting as ambitious—or in some cases more ambitious—than the narrative in film and television. As often as not, in 2007, 2008, 2009, if someone asked me what my favorite movie of the year was, the answer might’ve been a video game.”

One of those standout games was Fallout 3. Nolan described his first encounter with the game as a transformative experience. “I had one of those moments where you go, ‘What is this thing?’ At any given moment, it kept switching from ominous and violent to weirdly kind of gonzo and optimistic. I'd never experienced anything like it in film or television.”

That impression stayed with him. Years later, when Todd Howard reached out to discuss the possibility of adapting Fallout for TV, Nolan was immediately on board. “We just hit it off,” he said. “For me, there’s nothing more exciting than getting a chance—and I’ve had it a couple of times in my life, first with Batman and now again with Fallout—to wind up playing in a space I’d inhabited as a fan.”

A New Revolution

When discussing the early stages of adapting Fallout for television, Nolan reflected on the challenges of translating video games to the screen. “I still think of myself as quite youthful,” he began. “For me, this really does feel like my second rodeo, and it’s kind of amazing to now be embarking on what feels like a second complete cycle of the entertainment business.”

He drew parallels between the evolution of video game adaptations and the comic book movie revolution of the early 2000s. “I wasn’t there on the ground floor of the comic book movie revolution—you’d call it the Mezzanine,” he said. “There had always been outstanding comic book adaptations, from Dick Donner’s Superman films to Tim Burton’s Batman in 1989. But in 2000, it was still a bit of an uphill struggle. When I started with my brother in 2003 on Batman Begins, Chris’s pitch was, ‘We want to do a grounded comic book movie.’ That was quite an unusual proposition at the time.”

Nolan sees history repeating itself with video game adaptations. “Now I’m seeing this sort of déjà vu all over again,” he said. “The industry is going through the same growing pains, but I think we’re at the beginning of a really exciting moment for these stories.”

The Video Adaptation Game Curse

Reflecting on past missteps in video game adaptations, Jonathan Nolan said, “Some of the early attempts to adapt video games got fixated on the idea that it has to be in the first person. Movies have been around for a hundred years, and there are only a handful of films that are told in the first person. It doesn’t quite fit with the grammar of film. The flip side of that is, when I play games, I don’t like to play in the third person. For me, the natural grammar for video games is first person. It just speaks to the differences between these mediums.”

For Nolan, the key to any adaptation is finding the essence of the story without being overly rigid about the source material. “I think you have to come from a place of passion for it, but not pander to it—not imagine that you have to check certain boxes,” he explained. “What you’re really looking for, in any adaptation, is to know something, love it, and then look for the essence of it. You have to give it the respect and dignity to question what won’t survive the adaptation. That’s especially challenging with video games because you’re taking away interactivity and replacing it with reality. Not an easy challenge, but we’re delighted that people seem to have responded well to this one.”

Walton Goggins, sitting alongside Nolan, offered high praise for his work on Fallout. “I’m going to tell you—when I saw this for the first time, we were in Brazil, watching the first two episodes. I left that experience, and he wasn’t in the room—why would he be?—and I just walked out thinking, ‘Where is he?’ I couldn’t believe what you accomplished, man,” Goggins said. “You fundamentally, at one point, just firmly planted a cleat and changed directions, and you did it with such grace. It was effortless, man. The pivot you made to comedy, and the way you captured this tone, I’ve just never seen you do that before. And I’m a student of what you’ve done.”

He continued, “I just have to say that, because I’m sitting here next to the man, and he’s a friend of mine. I don’t think it’s been said enough, so there you go.”

Nolan, clearly amused by the praise, replied with a grin, “Well, you’re very kind. I think my approach remains the same—hang out with supremely talented people and then take credit for their work.”

Becoming the Ghoul

Walton Goggins hadn’t heard of Fallout before joining the series, but the role of The Ghoul—an irradiated, centuries-old survivor—quickly became one of his most fascinating characters to date. As a gamer myself, I had to ask him about his experience with the Fallout series.

“Great question, and no, I had never heard of the game Fallout,” Goggins admitted. “I’m not a gamer. I stopped at Pong.”

What drew him in wasn’t the game itself, but the powerhouse creative team behind the series. “What I did know was the people behind this project: Jonathan Nolan, Geneva Robertson-Dworet, and Graham Wagner. And it’s like, wow, that’s a powerhouse. Okay,” he recalled. “We got on a call, and they told me about the world. And as I’ve said in the press, I almost said yes right there—without even knowing what I was agreeing to.”

But Nolan made sure Goggins fully understood the role before signing on. “Jonathan said, ‘Wait a minute. You’re going to play an irradiated, kind of nose-less cowboy who’s been wandering a post-apocalyptic wasteland for 200 years.’ And I said, ‘Well, maybe I should read those scripts.’”

Once he read the scripts, Goggins was hooked. “I thought, wow, this story holds up on its own. Whether it’s based on a game, a novel, or just someone’s imagination—it doesn’t matter. It felt like a myth, a story that could’ve been passed down over a thousand years.”

His son, a gamer himself, gave him new insight into the power of video games. “My son was 11 and a half when we started this, and he’s a bit of a gamer. He uses it to relax in such a positive way, and I’ve seen the impact of games on his life,” Goggins said. “I hadn’t played the Fallout games, but I knew it was important to understand their world. Jonah, Geneva, Graham, and Amazon are incredibly collaborative, and they wanted my ideas. I felt my ideas would be better if influenced by the game’s universe.”

What struck Goggins most was the global community that gaming creates—a realization that came to him during his travels. “What I didn’t fully understand was the global connection these games elicit. You can get that with a television show too, but with games, it’s something different. There’s a community that resonates so deeply with people who’ve been playing for a long time.”

“I was out of the country when the show launched. In Thailand, one of the grips on the set said, ‘Hey, I really like your show.’ Then we went to Istanbul, and in one street, I was stopped by someone from Kurdistan, then Iraq, then Syria. The next day, someone from Israel stopped me. I looked at my wife and said, ‘My God, this really is a global community.’ It’s people from all over the world, showing up and sharing this experience. And then there’s people like myself, who’ve never played the game, but still feel drawn to it.”

A Global Impact

“Oh, it’s extraordinary,” Jonathan Nolan said of the show’s reception. “You try not to worry too much when you’re working on these things about whether you’ll reach people, but it’s an extraordinary privilege to travel and interact with people who derived something from what you worked on. It’s very humbling to realize the reach of it.”

He credited Amazon’s global platform for making that reach possible. “It’s one of the things about our business that’s changed. These shows hit seismically around the world all at once, and it allows everyone to participate in a conversation together.”

Nolan goes on: “I grew up in the UK—my mom’s American, my dad’s British—and they argued for 42 happy years about where to live. We spent summers in Florida and the rest of the time in England. In the 1980s, every summer I’d go to the movies and see Back to the Future, Top Gun, Ghostbusters. But those were the days of the international window. American movies wouldn’t show up in the UK for maybe six months. So I’d go back to the playground and be the prophet of Hollywood. I’d pitch the stories: ‘You’re not going to believe this—there’s these three guys who catch ghosts, and they have a pet ghost that helps them.’”

Nolan believes that experience shaped his career. “I don’t think it’s an accident I became a screenwriter. That global conversation didn’t exist back then, but now it does. These shows arrive the same day, same hour, same minute, everywhere, and the ability for the world to talk about our work together is just extraordinary.”

Walton Goggins agreed, reflecting on his travels during the show’s release. “I felt like I was in a lot of different countries when this happened, and it reminded me of when the World Cup is on. You’re in some little café or bar, and everyone’s watching it on a tiny screen. I love watching the people as much as the game.”

He likened that feeling to Fallout’s global impact. “It’s not that I want to be sued, but I wish I had cameras on everyone watching Fallout, just to see their reactions. The world’s a big place right now, and people are finding something in it. I’m just so grateful to be a part of it.”

Cooper and the Ghoul

Playing both Cooper Howard and The Ghoul posed quite a challenge for Walton Goggins. “It was a journey, really,” he said. “There were conversations—Jonah and I talked about it a little—but he really left me to my own imagination to understand how these two people speak to each other over time.”

Goggins reflected on the series’ opening scene, which stuck with him from the moment he first read it. “It still haunts me. It haunted me when I read it by myself in a motel room in Wilmington, North Carolina. I couldn’t get it out of my head when we were filming it, and I still can’t get it out of my head today. It’s deeply personal, especially as a parent, and in some ways, it’s about experiencing the end of the world—for all of humanity, at least in our world.”

Cooper Howard, Goggins explained, embodies the best qualities of America. “He’s got this really laconic, super laid-back attitude, with a cool sense of humor. He’s the kind of person people want to hang out with.”

That humor, he said, is one of the few things The Ghoul holds onto after two centuries of witnessing humanity’s worst. “He’s carried the weight of seeing how horrible human beings can be to one another. You become anesthetized to that experience.”

Bridging the gap between Cooper and The Ghoul required Goggins to dig deep into their backstories. “What was Cooper Howard’s world? Who were the actors he was friends with? Where did he come from, and how did he stumble into this career? I think he was probably a stuntman,” he said. “Connecting that to The Ghoul—a person who, when he sees himself, is reminded of how far the world has fallen—that’s where the throughline is.”

He noted that The Ghoul is the only character who’s lived through both sides of the apocalypse. “He’s the one who’s seen it all. It was a real privilege to play that.”

And Cooper had one advantage over The Ghoul: “Being Cooper only required me to be in the makeup chair for about seven minutes. Those were good days—but in some ways, a little more painful.”

Fallout’s Social Commentary

Jonathan Nolan didn’t shy away from the social and political undertones of Fallout. “There’ve been various moments I would’ve happily been in a vault over the last couple of years,” he said. “We sat down with Todd Howard in the middle of 2019—or, as I like to say, three apocalypses ago.”

At the time, the idea of a resurgent Cold War and nuclear threat felt almost nostalgic. “And sadly, by the time we released the show, you’re at a point where you say, ‘Okay, enough relevance. We don’t need to be any more relevant. Please.’”

Nolan reflected on the balance between storytelling and social commentary. “I’ve long felt, when we work with properties like Batman, that you have to be careful not to politicize too much. I don’t feel like I have that much to offer people in terms of telling them what to think. I don’t ever want our work to be didactic. But I do think our work can pose really interesting questions, and that’s where I’m most comfortable.”

With Fallout, however, the tone of the source material encouraged a bolder approach. “The games are quite aggressively satirical and political. So Geneva, Graham, Athena, and the rest of the team—and myself—felt emboldened to go for it a bit. Part of the appeal of the show is getting to watch what happens to these massive institutions when they’re put through the ringer of a nuclear apocalypse—and seeing what comes out the other side.”

For Nolan, much of the commentary comes in the form of questions. “I think there’s also a cautionary tale here. People these days talk very cavalierly about war, civil war, the end of the world. Politicians talk in apocalyptic terms. And I think, to the degree that the show has a message, it’s this: Be careful what you wish for.”

He paused before adding, “There’s an awful lot of beauty in our world. Sure, there’s horror, and there are things we still need to figure out. But we have a lot going for us. It would be awfully sad if we threw it all away.”

Nolan downplayed the “visionary” label that has followed him throughout his career. “My brother always cautioned me to never let anyone call me a visionary, because it’s the last compliment you get before your career is over.”

Directing the Post-Apocalypse

Jonathan Nolan reflected on his journey from writer to director and the impact his brother, Christopher Nolan, had on his approach. “Growing up with a director in the family, I always felt like words were my end of things. Chris and I collaborated on half a dozen movies over 15 years, and working with a great director—seeing your vision translated from the page to the screen—was a great joy for me.”

He recalled the pivotal moment that pushed him toward television. “I’d gone through this rough, long-haul process on Interstellar. I started it with Steven Spielberg and the incredible Lynda Obst, who hired me to write the script along with Kip Thorne. I spent four years going to lunch every other week with Kip at Caltech, trying to learn the theories of relativity well enough to communicate them to an audience. And then, halfway through, Steven had to leave the project because Paramount and DreamWorks had a corporate divorce. Suddenly, I found myself dead in the water.”

Two things happened next. “First, I thought, ‘Well, I know a guy.’ I reached out to Chris to see if he’d be interested in the project. I was emotionally attached at that point and wanted it to be seen. And second, I looked at my wife’s experience in television, and boy, did that look appealing. I’d spent four years on one movie, only to face the possibility that all that work might go nowhere. Meanwhile, she was working on shows with 23 episodes a year. It felt like speed chess.”

That shift drew Nolan toward television, where he found a medium that allowed for deeper storytelling. “In TV, you have room to explore character in a really rich way. There are always things in movies that don’t make the final cut, but with TV, you have time to go deeper.”

Directing was both a necessity and a revelation. “I didn’t have the benefit of my brilliant older brother directing anymore. I had to figure out how to do it myself. And then I realized that I really enjoyed it. It felt like the yin to writing’s yang.”

He compared screenwriting to creating a recipe without ever tasting the dish. “When you’re just writing, it’s like writing a recipe where you never get to touch the ingredients—you have to guess what it would taste like. But when you write and direct, you get to work with terrific actors, the crew, everyone. Writing can be an introverted, alienating process. Directing makes it collaborative.”

For Nolan, that collaboration is the most rewarding part of the job. “One of the best parts of my job is getting to sit and watch the most talented people do what they do best. It’s a real privilege.”

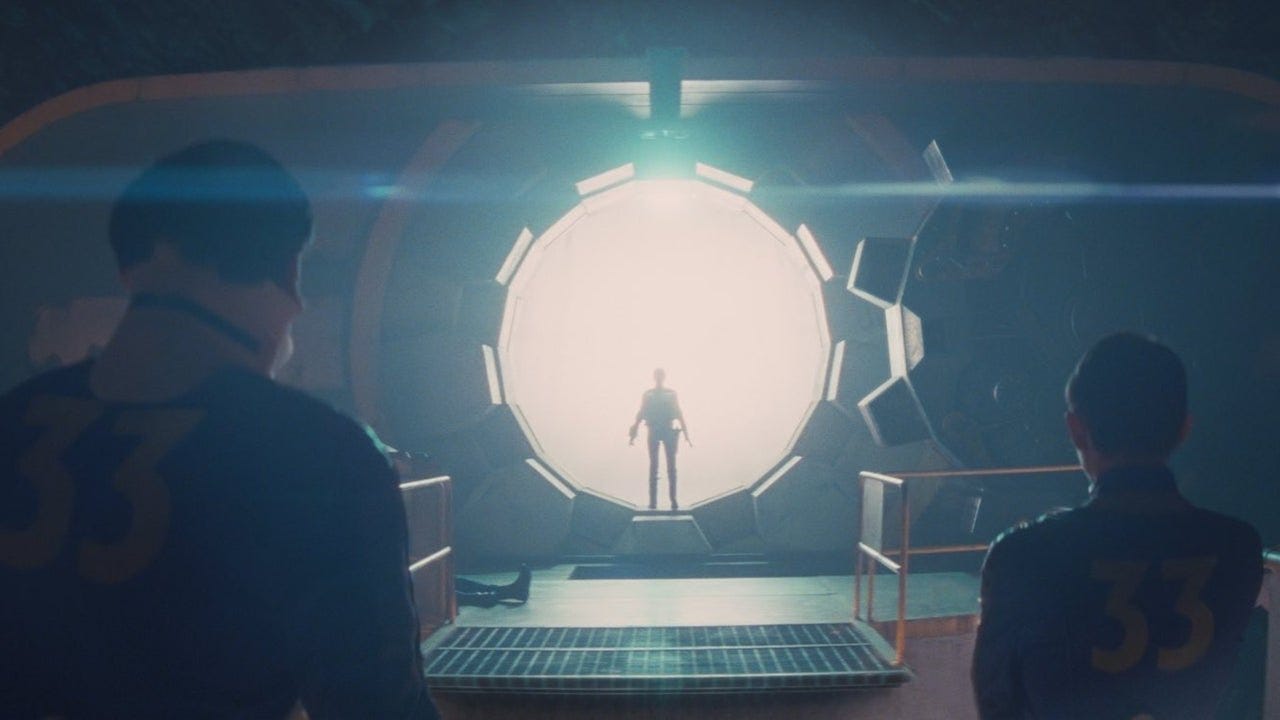

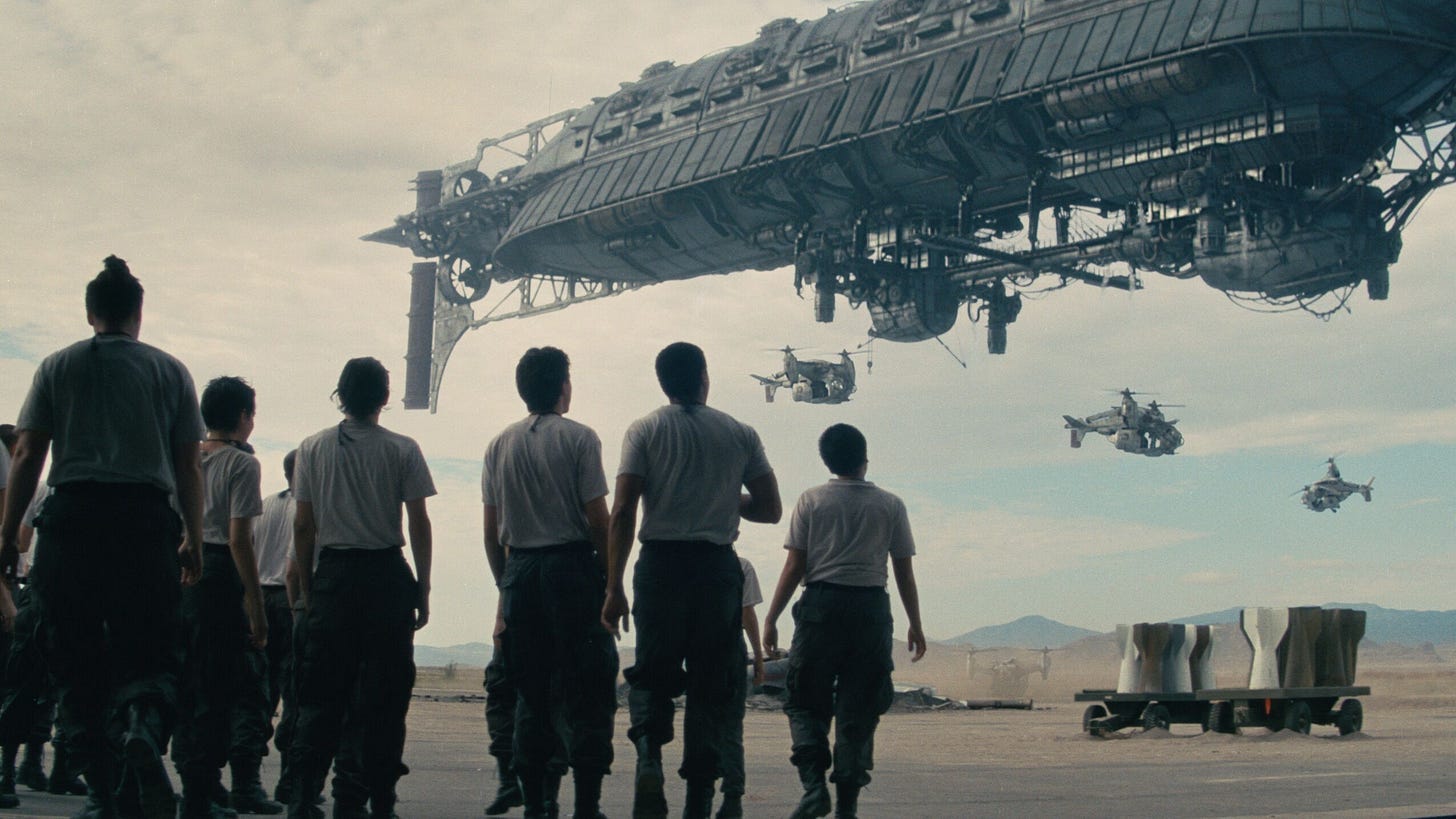

Building Fallout’s Wasteland

Walton Goggins admitted he didn’t expect the sets of Fallout to be as immersive as they were. “To be quite honest, I didn’t expect a tactile experience,” he said. “I’ve been around for a long time, and in my mind I thought, ‘Oh, you can’t really recreate the things I’m reading on the page. There’s going to be a lot of green screen, and I’ll just get used to that.’”

But that assumption changed the moment he walked onto the set of Philly for the first episode. “I had my gear on and everything, and I heard all this noise. I thought maybe they’d just broken for lunch or something. I didn’t really understand what was going on. No one took me on a tour beforehand.”

When he finally stepped onto the set, it took his breath away. “I really couldn’t believe my eyes. This world was fully three-dimensional—almost four-dimensional, if you take into account how it made me feel. Everywhere you looked, the attention to detail, the homages to the game… but not overly so. It felt real and hyper-real. Absurd and grounded simultaneously.”

That attention to detail was consistent throughout the entire shoot. “The ship at the beginning of the show, the places Ella walks around—we went there. We went to Namibia. It wasn’t green screen. Jonathan said, ‘No, we’re going to these places.’ And it fundamentally affects every decision you make, how you feel when you go to work.”

Goggins paused, hinting at the production’s next steps. “I know it’s no secret that we’re back—or close to being back, right?”

“We’re back now,” he continued. “I felt it yesterday. And Howard is so extraordinary at his job, along with all the artisans who work on this. But it was this man,” he said, motioning toward Nolan, “who made that happen. He said, ‘I’m not going to settle for anything less than that.’ And we’re all better for it.”

And there it is. Fallout will be back for another season—which is no secret—and this time, we’re headed to New Vegas (nerds, rejoice!). With the show’s initial success, it seems likely there will be many more seasons to come.

I can’t wait!